By David Haldane

Dec. 11, 2023

A transgender friend said something recently that I’d been thinking but was afraid to say out loud.

“Miss Universe allowing transgenders?” she exclaimed. “We have our own pageants. I’ve never heard of a trans pageant allowing genetic women, so why should Miss Universe allow a trans?”

Her comment took me back to the Miss Gay Pilar Universe pageant of 2017, the only transgender beauty contest I’ve ever attended. Pilar is my wife’s hometown on Siargao Island, where our principal contribution was a fancy pair of high heels to help her barangay’s contestant win.

She didn’t.

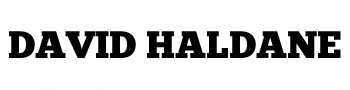

But we ended up spending three hours in a standing-room-only crowd having the time of our lives. For starters, the event took place in a huge gymnasium wherein the 15 contestants were judged by a panel of local dignitaries, including the mayor. And I found myself on fairly familiar ground; it was an almost blow-by-blow parody of the bigger international Miss Universe pageant that recently enthralled Filipinos nationwide.

The contestants were judged prancing about in evening gowns, bathing suits, and regional ethnic costumes. They were also asked to exhibit their talents and answer pointed personal questions. And, as always, I was struck by the charming enthusiasm displayed by the audience, a warm attitude of acceptance I have come to associate with the Philippines.

“This is a culture,” I later wrote, “imbued with a natural sense of acceptance and friendliness towards, not only strangers, but the strange.”

Which struck me as ironic, given the Philippines’ long association with a Catholic Church that, until recently anyway, didn’t look kindly on any form of what it considered sexual deviance.

Transgenderism is certainly less “strange” today than it was even six years ago. And yet, I can’t help but feel a little disappointed at what Miss Universe seems to have become. Historically, and by definition, it was always one of the world’s most exclusive “clubs.” Now, it appears, the goal is exactly the opposite: to become a model of inclusivity. This year’s pageant, besides two trans candidates, included a “plus-size beauty queen” and two married “misses” with kids. Does this mark the end of what the pageant has historically represented? And can the pageant Filipinos know, and love survive such a radical change?

My daughter, a 39-year-old newspaper editor and country singer in Portland, Oregon, thinks the widening inclusivity may, in fact, provide the very key to the pageant’s survival. “They are reaching out to new audiences,” she maintains. “Every woman has her own kind of beauty. The greater number of people who can see themselves on that stage, the more popular the pageant will become.”

An informal survey of Filipino friends and relatives strongly disagreed. Virtually everyone opposed the participation of married mothers, and almost everyone felt the same about transgenders. Only plus-sized women got a pass.

I remain stubbornly on the fence. On the one hand, larger-framed and trans women don’t fall within my sense of what constitutes feminine beauty. On the other, well, maybe — just maybe — they should.

The real question, though, is this: can a beauty pageant survive based on different—and sometimes conflicting—standards of beauty? Or, finally, is there really only one? Every woman has her own kind of beauty, yes, but by what common standards can it be judged?

And, of course, one might also question the slipperiness of the slope on which the pageant is perched. If trans, plus sized, and married contestants are allowed today, who will be allowed tomorrow; disabled, scarred, or misshapen? For they too have their own kind of beauty, do they not?

I wait, with bated breath, for Miss Universe fans — and history — to settle the matter for good.

_________________________________________________________________________